Find your winery or vineyard

Infographic of the Denomination of Origin

Change to imperial units (ft2, ac, °F)Change to international units (m2, h, °C)

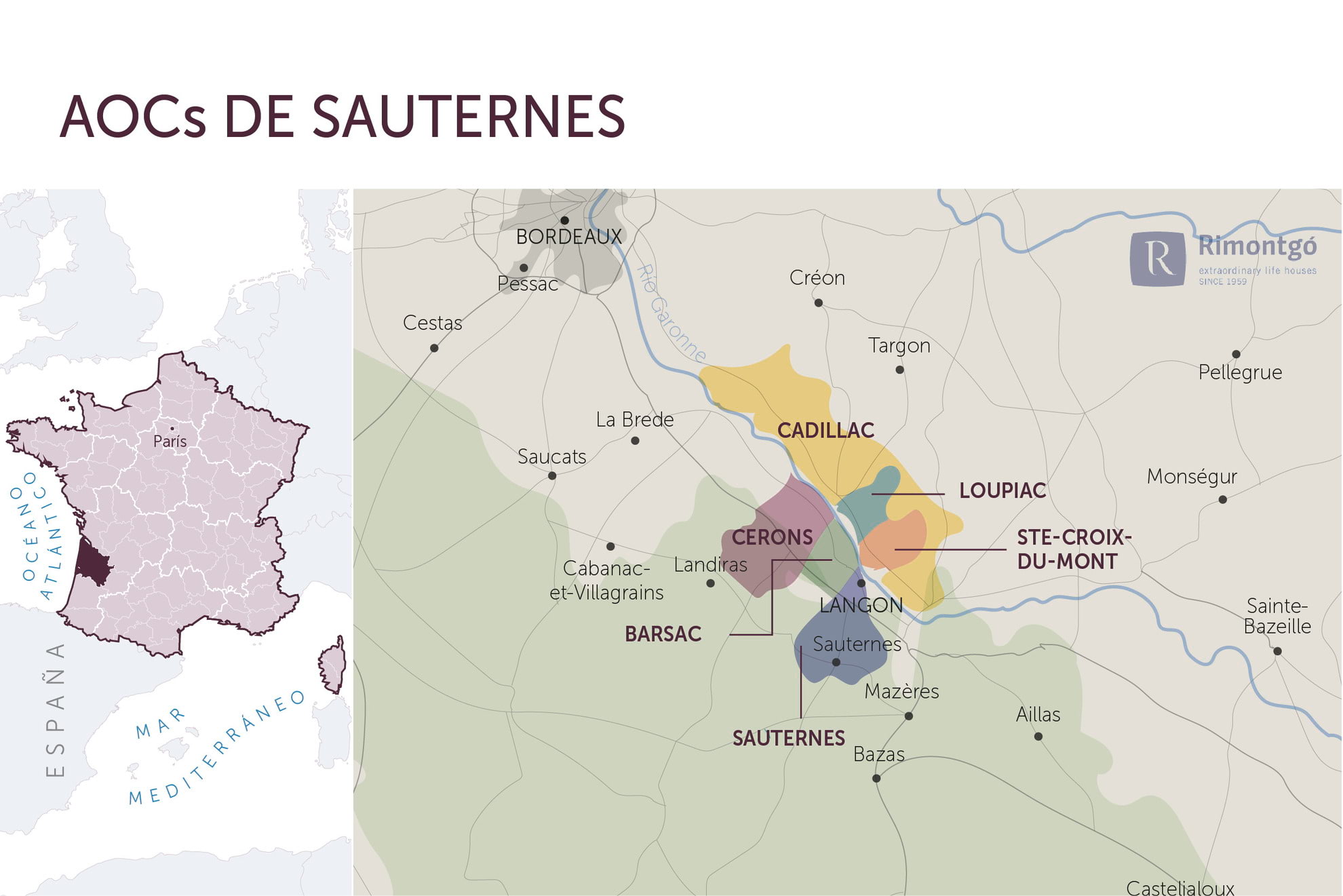

AOC Sauternes / AOC Barsac / AOC Loupiac / AOC Cadillac

How many writers have been delighted by a sweet wine and have written about it in history! Its brightness, its light, its diffuse colours, its aromas, its taste, wines that comfort the soul. These golden reflections are often compared to the shine of gold jewellery, to precious stones such as citrine quartz, topaz, amber or simply to the light of twilight.

The most prestigious of all sweets is Château d'Yquem. Proust, Dumas, Mauriac, Colette, Jules Verne approached this world through their letters.

The intensity of the golden layer of these exceptional wines deceives about the age of the wine, its origins and the concentration of sugars. The wines from Cadillac, Loupiadc and Sainte-Croix du Mont, generally less concentrated, have a less intense robe than their neighbours from the AOCs on the other side of the river, Sauternes and Barsac, and show in the early years slight green reflections in the aureole. They also have a less dense, less oily appearance than the wines from the left bank. This does not prevent them from taking on darker tones in a few years. The ageing in wood barrels also contributes to the creation of this colour.

But it must be said that the greatest Sauternes and Barsacs defy time. After decades in the bottle, they show amber tones close to cognac and armagnac. Dense and bright reflections reminiscent of summer light.

Hard to resist these nectars with amber reflections and intense, baroque aromas reminiscent of exotic fruits, flowers, spices and citrus fruits. Because these wines are made from grapes where the botrytis cinerea fungus is present, their aromas are more complex and with more varied aromatic registers.

The wine is intense and with a great explosion of aromas. The wines of Cadillac and Sainte-Croix-du Mont, rather elegant and refined, develop aromas of citrus fruits, white flowers such as lime, honey, but have a less exuberant nose. Loupiac, slightly more concentrated, has a slightly more intense nose. And finally the Sauternes and Barsac are more concentrated than the other wines, with notes of ripe, candied fruit, mainly contributed by the white grape variety Semillon, with its opulent character that is in the DNA of the great sweet wines of the region. It is often the majority variety in wine blends or even the only grape used, as in Château Climens in Barsac. Sauternes can sometimes seem more toasted than Barsac, but it shines with a flash of freshness due to its citrus character, particularly noticeable on the palate.

Sweet, opulent, lush, sweet, intoxicating, magical, gourmet... there is no shortage of epithets to describe the sweet wines of Bordeaux on the palate.

The harmony in the wine reveals its origins, the breed and nobility of a wine. In the great years, Loupiac and Sainte-Croix-du-Mont are reminiscent of Sauternes and Barsac, the structure and concentration are simply different.

Cadillac wines, less dense, are fresher and livelier on the palate, especially if they have a higher proportion of Sauvignon Blanc. The wines from Loupiac and Sainte-Croix-du-Mont are more structured. The palate is opulent, with aromas of ripe fruit, citrus and dried apricot (a characteristic note of botrytised grapes) that sweep across the palate. Over time, notes of almond, dried fruit, gingerbread and honey complete the palette of aromas.

The palate is also a great witness to differentiate Sauternes from Barsac. The Barsac vineyards are located on a limestone plain, while the Sauternes vineyards are located on clay hills, similar to those of Yquem. These two terroirs produce different wines. The wines from Barsac are less oily or dense than their neighbours, but also complex, evolving on a different aromatic spectrum. They also exude notes of citrus fruits and flowers which give them a pleasant freshness on the palate. In contrast, Sauternes wines are monuments of opulence and density. However, the greatest ones, which take twenty years to fully appreciate, display a palette of aromas so extensive, precise and complex that it never quenches the thirst to discover more of their mystery.

THE VINEYARD

Their rarities, atypical aromas and complexity of production give these sweet wines a special status in the world of wine. In the Bordeaux vineyard, about ten AOCs produce them, but Sauternes, Barsac, Loupiac, Cadillac and Sainte-Croix-du-Mont are the main ones.

In Bordeaux, the production of sweet wines is concentrated in the south of the Gironde department, on both banks of the Garonne river. If a dozen AOCs can produce them, six of them produce exclusively liqueur wines (Sauternes, Barsac, Cérons, Saitne-Croix-du-Mont, Loupiac and Cadillac) which have a high concentration of sugars. This type of wine is the most difficult and most expensive to produce.

The particular climate on the banks of the Garonne is a fundamental element in the transformation of the grapes into nectar. From the first frosts in autumn, the mist from the river covers the region's vines. They favour the development of a strange fungus, Botrytis Cinerea, on Semillon, Sauvignon Blanc and Muscadelle grapes (the most marginal variety in the blend), which are the three authorised varieties. This noble rot favours the dehydration of the grapes, which concentrate their sugars spectacularly from the end of September to November. This miracle of nature is extremely fragile and with just one rainy autumn the harvest can be destroyed as the fungus turns into grey rot instead of noble rot, which is totally harmful for wine production.

As an example, we can say that a vineyard of Château d'Yquem will give less than a glass of its exceptional wine. By comparison, a red vineyard produces five times this amount.

AOCs

Six AOCs dedicated to sweet wines that are differentiated by their terroir, surface and regulation: Sauternes, Barsac, Cérons, Cadillac, Sainte-Croix-du-Mont and Loupiac.

Barsac: the wines produced in the Barsac area can benefit from the AOC Barsac as well as the AOC Sauternes, but not the other way round. With an area of 496 ha in production, this appellation is the most prestigious of all after Sauternes. It is distinguished from its neighbour by its hilly terrain, which lies on a limestone terrain. The border with Sauternes is marked by the river Ciron, a local tributary of the Garonne. The two AOCs share the same production difficulties. Yields cannot exceed 25 hl per ha, which leads producers to produce more concentrated wines than those of Cadillac, Loupiac, Cérons or Sainte-Croix-du-Mont. Barscac has nine Crus Classés.

Cadillac: the AOC Cadillac area, which extends over the southern half of the AOC Prémières Côtes de Bordeaux, seems huge compared to its neighbours, but in reality it has no more than 70 wineries and 209 ha of vineyards in production. To obtain the AOC Cadillac, the wines must contain a minimum of 211 gr of residual sugar per litre and after fermentation a minimum of 12º of alcohol and a residual sugar of at least 18gr per litre. The yield must not exceed 40 hl per hectare of vineyard in production. These rather easy conditions explain why their wines do not reach a concentration comparable to Sauternes or Barsac although the same varieties Semillon, Sauvignon Blanc and Muscadelle are used.

Cérons: located on the left bank of the Garonne river, north of Barsac and Sauternes, the AOC Cérons is in fact the smallest AOC producing sweet wines, 57 ha, but it is also one of the oldest AOCs. It has the same qualities and conditions as Cadillac, with the only difference that the wines must have a minimum alcohol of 12.5º.

Loupiac: located on the right bank of the river, between Cadilla and Sainte-Croix-du-Mont, the AOC Loupiac extends over 347 ha in production and has 70 winegrowers. It is located on hilly but not very high limestone slopes that allow the vines to catch the mist from the river, which is favourable to the development of botrytis. Like its neighbours, it has the same conditions and the same varieties.

Saint-Croix-du-Mont: it covers an area of 389 ha, on the most rugged terrain of this part of the right bank of the Garonne. The conditions are similar to those of Loupiac and Cadillac. The difference between the wines of these three right bank regions comes from the nature of their relief.

Sauternes: the most prestigious of the sweet wine AOCs and also the largest. It covers 1,751 ha of vineyards in production. Its terroir is different from that of Barsac, more hilly, with a higher point at 80 m above sea level, located to the east of Château Rieussec which is made up of a succession of clayey pebbly ridges surrounding the hill of Château d'Yquem. An exceptional terroir for the production of great sweet wines. This AOC has 17 crus classés representing 40% of the total surface, which represents its strength and notoriety.

SOILS

The AOCS that produce the sweet wines of Bordeaux extend along both banks of the river Garonne. The left bank is less stormy than the right bank.

From the first cold mornings in September, the mist from the Garonne and the Ciron (the tributary that separates Sauternes from Barsac) flows along both banks to encourage the development of botrytis in the vineyards. The geography of the site lends itself perfectly to these ideal climatic conditions. To understand this climatic phenomenon, we need to understand the physiognomy of the site and the nature of the terrain. The river forms a large basin, breaking up into successive terraces on which the vines are planted. The nature of the soil, especially in the lower part, based on limestone and clay, favours water retention and consequently increases the level of humidity. This moisture reappears in autumn, in the form of mist, when the temperature difference between day and night is high.

As can be seen, the nature of the relief between the two banks is radically different. While in Sauternes the slope is gentle and regular up to an altitude of 80 m, on the right bank, the slopes rise rapidly to over 100 m in Sainte-Croix-du-Mont, this being the most rugged AOC.

The soils are also different, in Sauternes the main properties such as Rieussec, Yquem, Suduiraut, Giraud... are perched on clay hills with pebbles ideal for the production of great sweet wines with complex and balanced aromas. Terroir that is not found in the lower part of the AOC. On the right bank, the AOC Sainte-Croix-du-Mont lies essentially on rocky soils composed of limestone and clay, with a south-west exposure. There is also the spectacular oyster bed, a considerable pile of fossilised shells, which can be seen below the church and the village castle. These are traces of life from the Lower Miocene (20 million years ago) when the ocean submerged part of this region.

WINEMAKING

To transform the grapes into gold, the wineries wait patiently for the berries to become covered with noble rot, "Botrytis cinerea", a fungus that is essential for this transmutation. Thanks to this fungus, the grapes rot and the sugars are concentrated, allowing a divine nectar to be produced.

Without a doubt, the most noble sweet wines are those made with botrytis, the most seductive to the eye and the most gourmet on the palate. At once smooth and opulent, they express an incomparable symphony of aromas. It is also the most difficult wine to make because there are many risk factors both in the ripening of the grapes and during vinification and ageing. Moreover, the low yields that can be obtained from one ha are so low that they are the most expensive wines to produce.

It all starts in the vineyard. While white grapes destined for dry white wines are the first to be harvested, this is not the case for grapes destined for sweet wines. From September onwards, a climatic phenomenon occurs on both banks of the Garonne river, the morning mist will dampen the vines of the AOCs close to the river and encourage the development of a fungus, a mould on the bunches, botrytis cinerea. Also called noble rot because this fungus alters the aromatic qualities of the grapes, but brings a broader spectrum of aromas. However, the fungus becomes permeable through the grape skin and within several weeks dehydrates the grapes and concentrates the sugars. When the grapes are harvested, which must be done by hand, the harvester selects the most botrytised berries and leaves the rest to be harvested later, this is called the tría. Depending on the vintage, Sauternes grand crus can have three to six successive trías spread over several weeks.

Once the grapes enter the cellar, they are immediately pressed and the must goes into stainless steel tanks or barrels to begin fermentation. The most rigorous châteaux do not collect more than a few hl of wine in one ha. It is for this reason that these wines are expensive and scarce.

As the concentration of sugars is high, fermentation is slow and takes a long time during the winter. Once finished, the wine is aged in oak barrels for several months, up to two years in the case of some grand crus such as Château d'Yquem.

HISTORY

Over the last two centuries, the Bordeaux vineyard has undergone a phenomenal evolution, from the birth of the first classifications to the global success of its wines and the arrival of the AOCs.

From the second half of the 18th century onwards, the first wines of what was to become a symbol of the modernity of Bordeaux wines made their appearance. The first classification of the best cellars was established by the Bordeaux wine courtiers. They are not yet official, but they constitute excellent commercial arguments. It clarified the offer and imposed a notion that was to be amplified throughout the following century, the notion of Château, which defined a wine-growing and winemaking entity. During the first half of the 19th century, Bordeaux wines went through difficult economic periods, especially due to the Napoleonic conquests.

It was in 1855 that the classification of Gironde wines was established, on the occasion of the Universal Exhibition in Paris, a moment of renewal for Bordeaux wines. The hierarchy of the wines presented brought a new look at Bordeaux for the tens of thousands of visitors who came from all over the world to discover Paris and its Universal Exhibition. The best Gironde wines were then classified, according to their selling price, into five categories for red wines and three for white wines. Of the reds, only Médoc wines and Château Haut-Brion en Graves are considered worthy of inclusion on the list. Among the whites, Sauternes reigns as the absolute winner. The wines of Saint-Emilion and Pomerol (dependent on the chamber of commerce of Libourne) then only represent a secondary category for the Bordeaux business.

From the 1850s onwards, thanks to the arrival of the railway, Bordeaux wines regained their success. Although diseases such as powdery mildew and downy mildew began to appear, the success of Bordeaux wines began to take off. But it was the phylloxera disease from 1865 onwards that changed the situation. Stocks dwindled and the shortage was compensated by massive imports of wines from Spain and North Africa. This competition was concentrated at the beginning of the 20th century with its abundant harvests. This overproduction caused prices to fall and ruined many wineries, unable to survive after years of fighting phylloxera. But Bordeaux is not the most affected area. Languedoc was going through a very dark period. After bloody revolts, in 1908 the public authorities drafted the bases of a geographical delimitation of production, the ancestor of today's AOCs, which finally appeared in 1935.

The two world wars and the economic crisis of 1929 suffocated the Bordeaux vineyards. Between the two wars, almost all the 1855 crus classsés, affected by the crisis, changed hands. After 1945, the recovery of Bordeaux proved difficult, the value of the wines was low and some crus even abandoned the cru classé label. In 1956, frost destroyed a quarter of the Girondin vineyard, a disaster that allowed the vineyard to be modernised on a large scale and more productive vines to be planted. It was not until the early 1980s that Bordeaux was successfully revitalised and established itself in the firmament of world production. In 1999, Saint-Emilion became the first vineyard in the world to be listed by Unesco as a World Heritage Site. And today, if Bordeaux produces some of the most prestigious and expensive wines in the world, it is also one of the few regions capable of producing quality wines at reasonable prices.

THE CLASSIFICATION

In order to best present the wines of the Gironde at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1855, the Bordeaux Chamber of Commerce established a classification according to the criteria of the wine courtiers based on the average price of the wines over the course of the last few vintages. Two classifications are established, one for red wines (only for Médoc wines and one cru de Pessac, Château Haut-Brion) and one for white wines where Sauternes wines are the only ones represented. 26 crus from Barsac and Sauternes are divided into 3 categories, where the most prestigious is Château d'Yquem classified as Premier Cru Superior. After 1855 this classification has never been modified.

Premier Cru Superior

Château d’Yquem (Sauternes)

Premiers Crus

Château Climens (Barsac)

Château Clos Haut-Peyraguey (Sauternes)

Château Coutet (Barsac)

Château Giraud (Sauternes)

Château Lafaurie-Peyraguey (Sauternes)

Château Rabaud-Promis (Sautenes)

Château de Rayne Vigneau (Sauternes)

Château Rieussec (Sauternes)

Château Sigalas Rabaud (Sauternes)

Château Suduiraut (Sauternes)

Château La Tour Blanche (Sauternes)

Seconds Crus

Château d’Arche (Sauternes)

Château Broustet (Barsac)

Château Caillou (Sauternes)

Château Doisy-Dëne (Barsac)

Château Doisy-Dubroca (Barsac)

Château Doisy-Vedrines (Barsac)

Château Filhot (Sauternes)

Château Lamothe-Guignard (Sauternes)

Château Lamothe (Sauternes)

Château de Malle (Sauternes)

Château Myrat (Barsac)

Château Nairac (Barsac)

Château Romer du Hayot (Sauternes)

Château Suau (Barsac)

Discover more wineries and vineyards for sale in these wine regions in France

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive news about wineries and vineyards.