Find your winery or vineyard

8 Wineries and Vineyards for sale in Les AOC du Languedoc

A WINERY WITH 35 HECTARES OF ORGANIC VINEYARDS.

DOP COSTIÊRES DE NIMES

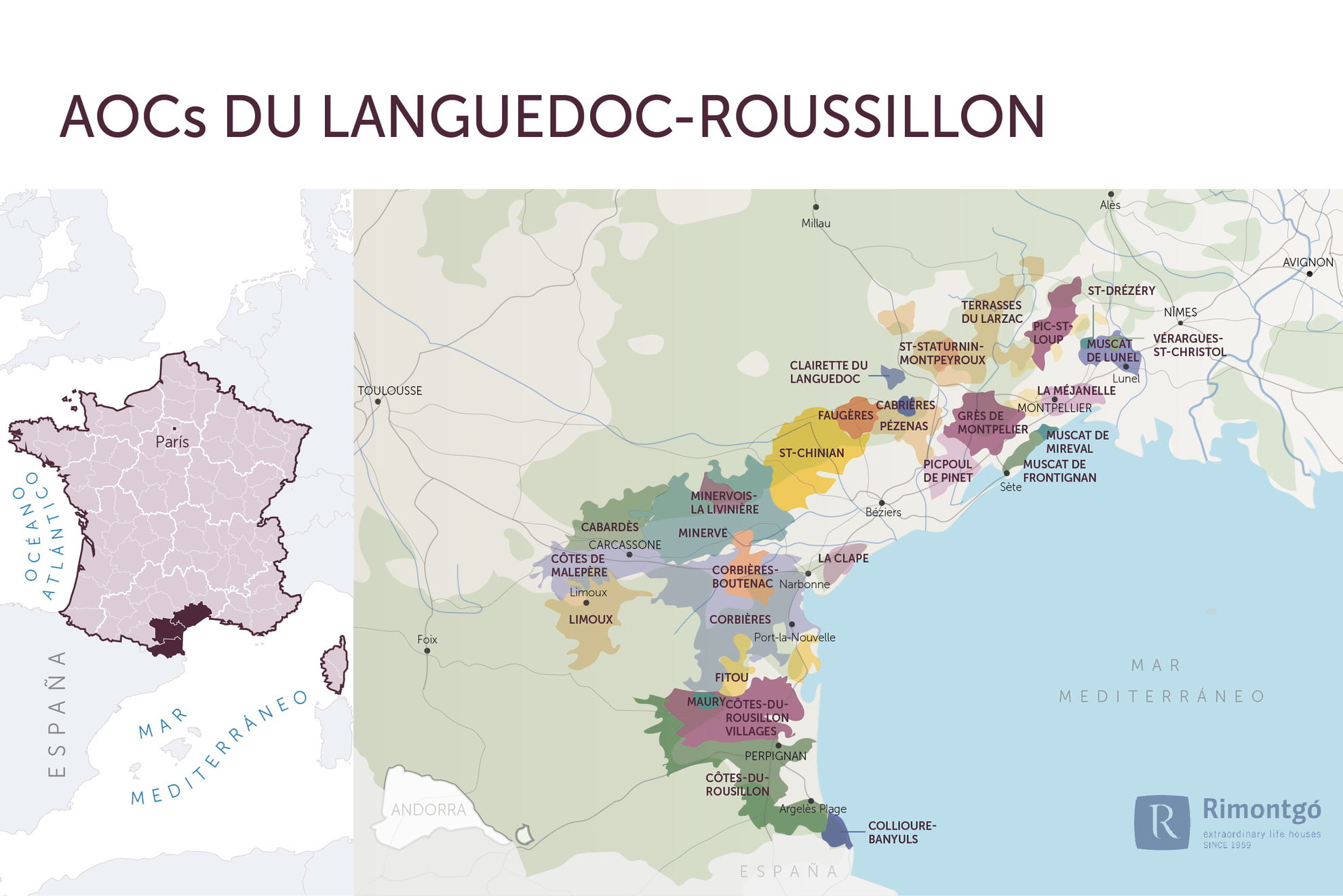

Infographic of the Denomination of Origin

Change to imperial units (ft2, ac, °F)Change to international units (m2, h, °C)

AOCs Languedoc

HISTORY

Founded by the Greeks, developed by the Romans, the Languedoc vineyard has grown over the years, to the point of being the wine cellar of working-class France for almost 50 years before initiating a qualitative turnaround that is celebrated today by many amateurs.

Vine culture seems to have its origins in the Greek colonies that conquered the Mediterranean, but it was not until the 2nd century BC and the arrival of the Romans that viticulture really took off. From then on, the Via Domitia was created between the Rhone and Spain around 110 BC and the region of Narbonne experienced unprecedented success, becoming the privileged transit point for the import of Roman wines to the west of Gaul. This passageway would allow the emergence of viticulture in the regions close to the south-west (Toulouse, Gaillac, Cahors, Bordeaux, Charente) throughout the centuries and throughout the presence of Rome. Unfortunately, the fall of the Roman Empire precipitated the economy of Languedoc, which was heavily dependent on its trade with Rome.

Peace returned with the monks, Benedictines and Cistercians; whose abbeys served as the basis for the recolonisation of the country. The vineyards regained their rights: the wines of Lagrasse and Fontfroide even seduced Charlemagne's sommelier. Unfortunately, the Albigensian or Cathar crusade, which came to exterminate the Cathar heresy, broke this good momentum once again.

The vineyard did not recover, with competition from neighbouring regions, Languedoc was content to produce wine for local consumption. The 100 years’ war and then the wars of religion abandoned the vineyard. With the peace of 1598, the region regained hope, the growth of the population, with an outlet to Spain and Italy, encouraged the producers to plant massively on the hillsides. The period from 1600 to 1660 was a golden age, but overproduction lurked and no market other than the Mediterranean basin could absorb the supply. Languedoc found itself in competition with the Bordeaux region which controlled the river traffic on the Garonne. A new period of recession came to Languedoc.

Prosperity did not return until the 18th century, with the boom in communications which broke the isolation of the Corbières thanks, in particular, to the construction of the Canal du Midi. But it was not until the arrival of the train in Perpignan in 1858 that viticulture underwent a real transformation. The train made transport considerably cheaper and Languedoc was in a strong position to start mass production. Between 1852 and 1875, the vineyard area increased from 294,000 ha to 463,000 ha. A record, but hatred and phylloxera took their toll. At the beginning of the 20th century, it became the largest vineyard in France, accounting for 40% of the national production, so much so that a year of peak production became a year of national congestion. The 1899, 1900 and 1901 vintages were so voluminous that the national market collapsed. Moreover, the Languedoc wines were in competition with the wines of Algeria, also in massive production. The revolt of 1907 was in the making.

From 1905 to 1910, six bumper harvests followed one after the other, aggravating the crises in the Mediterranean vineyards. The problems of 1907 ended tragically with the death of several demonstrators during clashes with the army. This crisis was neither the first nor the last. Until the 1980s, the vineyard was oriented towards a mass production of table wines and local wines. Even today, this vineyard is still trapped in history with a current crisis that is forcing several thousand hectares of vineyards to be grubbed up. In 30 years, the Languedoc Roussillon vineyard has gone from 500,000 ha to 250,000 ha.

SOILS

On the different soils of the Languedoc, the grape varieties express themselves differently. On the pebbles of Saint-Christol, Monastrell can produce intense aromas of leather and spices mixed with black fruit aromas. While in the limestone soils of Pic Saint-Loup, Syrah in all its elegance and finesse in this exceptional terroir will develop notes of pepper, spices, cassis and violets and if the wine is young, woody notes may appear. Over time the red wines evolve towards aromas of cocoa, leather and game. Those wines with Garnacha Tinta are marked, after some years, with notes of tar and roast. But in general all these vineyards are more or less impregnated with the environment where the vines grow, so thyme, rosemary, laurel and undergrowth can be identifiable.

The appellations further away from the sea and located at altitude (sometimes 500 metres), as in some areas of Corbières, show wines from cooler and more delicate climates. The less dense tannins are silky and very fine. The soils of the AOC Corbières are a good example of the soils of Languedoc, close to the Pyrenees and on the southern foothills of the Massif Central, bathed by the Mediterranean, they show a great variety of soils.

This AOC Corbières has the double advantage of being large enough to offer a wide variety of terroirs and of stretching from the shores of the Mediterranean Sea to the edge of the city of Carcassone. The eleven terroirs that make up the appellation, including Boutenac, Sigean, Lagrasse, Quéribus, Lézignan and Serviès, respect the different types of soils that can be found. If we cut through the Sigean lagoon to the Pinède forest, near Boutenac, we will find the different types of soils that separate the terroirs of the appellations.

Before the existence of the Corbières Massif, the region was a peneplain where the soil was composed of limestone and slate. It is in the Cretaceous period, 100 million years ago, that the Iberian Peninsula moved towards the European continent and the reliefs of the Pyrenees, such as the Corbières Massif, were formed. This is the reason why the region is an uneven land, where small, rugged reliefs continually appear right down to the sea. Moreover, erosion has accentuated this diversity. In the arable areas, it is the clay-limestone soils that dominate, with variations depending on the terroir: red clay in Boutenac, pebble terraces in Lézignan, marl in Quéribus or Serviès, slate in the upper Corbières or coral limestone on the edge of the Mediterranean, as in Sigean.

Depending on the soil where the vines grow, the wines offer a very variable typicity. Moreover, the climate also has a determining influence. While the climate is warm and humid on the shores of the Mediterranean, the coolness and diurnal variations in temperature in altitude favour the creation of finer and more elegant wines (especially whites).

CLIMATE

Dominated by the Mediterranean influence and found in the typical scrubland vegetation. Certain terroirs, the most westerly, feel the oceanic influence.

WINERIES

Mas de Daumas Gassac, Domaine de L'Aupilhac, Mas Champart, Mas Jullien, Cols Marie, Domaine Peyre Rose, Domaine du Grand Arc, Mas de Martin, Domaine de Montcalmès, Château Oupia, Domaine Jean-Baptiste Sénat, Château La Voulte-Gasparets, Priéuré de Saint-Jean-de-Bébian, Domaine Léon Barral, Domaine Canet Valette, Domaine Cazes, Domaine de la Garance, Château de Jonquières, Domaine Borie la Vitarèle, Domaine del l'Ancienne Mercerie, Clos de l'Anhel, Mas Cal de Moira, Caves de vignerons de Camplong, Domaine la Croix de Saint-Jean, Domaine Maxime Magnon.

Discover more wineries and vineyards for sale in these wine regions in France

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive news about wineries and vineyards.